Twenty years after the Amistad incident, the Custom House Mairimte Museum was the setting for an Underground Railroad escape that pitted local abolitionist sentiment against federal authority.

It began when an enslaved man named Benjamin Jones fled his circumstances and attempted to gain his freedom.

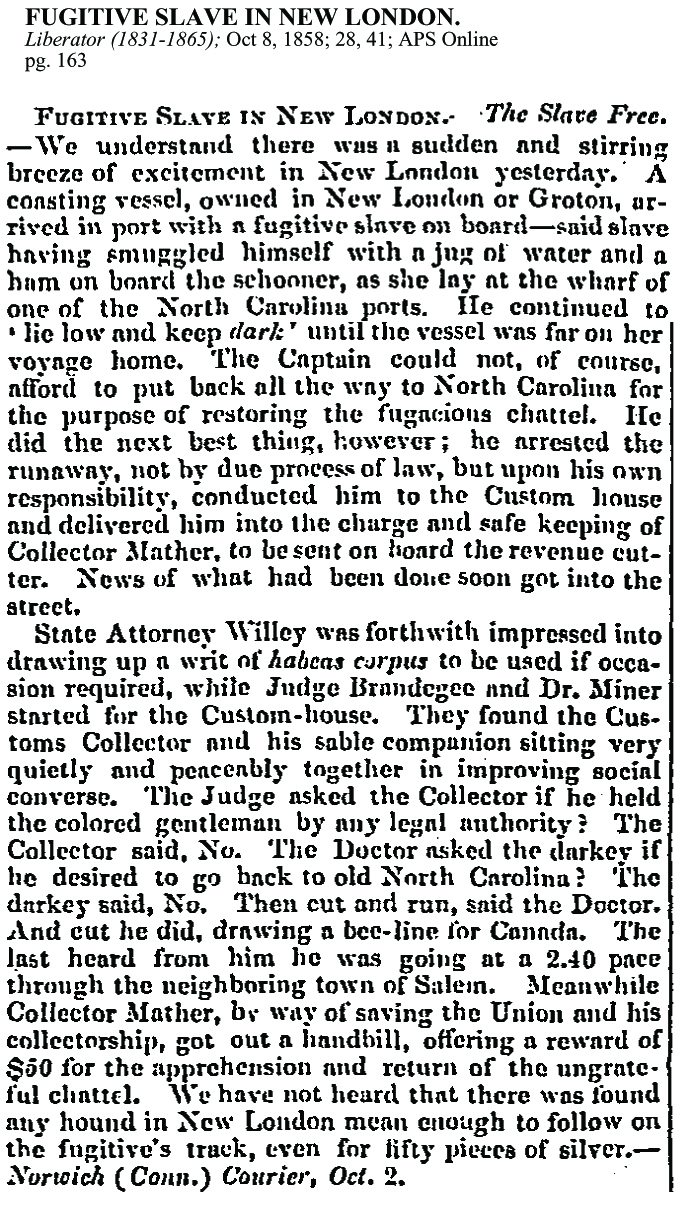

In the fall of 1858, the Liberator a national abolitionist newspaper caught wind of a fugitive slave that stowed away on Captain Josephus Potter’s lumber schooner the Eliza Potter. Captain Potter was down south buying lumber to bring back to New England. The stowaway slave smuggled himself on board while the ship was in port in Wilmington, North Carolina. One account said he had a jug of water and a ham, the other, two pounds of crackers and a piece of cheese. Either way “Stowaway Joe,” the name locals knew him as, did not have enough food to make the entire journey north to the Connecticut coast.

Days into the trip the fugitive, later revealed to be named Benjamin Jones, was discovered.

Captain Potter was in the business of lumber, not in the smuggling of fugitive slaves. He also was in business with the south, and quite unwilling to damage those relations; he kept the slave prisoner until the ship reached New London, Connecticut. Upon arriving in New London harbor the Captain headed towards the Customs house, which held the only federal government offices in the area for the Official to arrest his stowaway. When the men returned to the schooner the fugitive had escaped. The next day, Captain Potter spied Jones in a clothing store; he seized the fugitive and took him to the federal authorities at the Custom House.

The Collector of Customs was John P.C. Mather, a Yale-educated lawyer. Mather took Jones into custody under the 1850 the Fugitive Slave Act, which required that runaway slaves be returned to their owner, regardless of the location (state) within the Union where they were at the time of their discovery or capture. However, two years prior in 1848, the Connecticut Personal Liberty Law had prohibited slavery in Connecticut. This conflict seemed to have created confusion, or at least questions, about which authority reigned in the case of a fugitive slave. As word spread through New London about the Jones’s arrest, Police Court Judge Augustus Brandegee rushed down to the Customs House. He later described the events in this way:

“I immediately stepped within the rail which separated the parties from the crowd which had gathered, and asked Judge Mather if he was holding a court. His reply was to the effect that he was looking to see what his powers were. I then gave notice in a loud voice that, by the laws of the State of Connecticut, any man who claimed another to be a slave and could not prove it, was guilty of a crime; and if brought before me (and I was then judge of the police court) I should not require much evidence to find him guilty.”

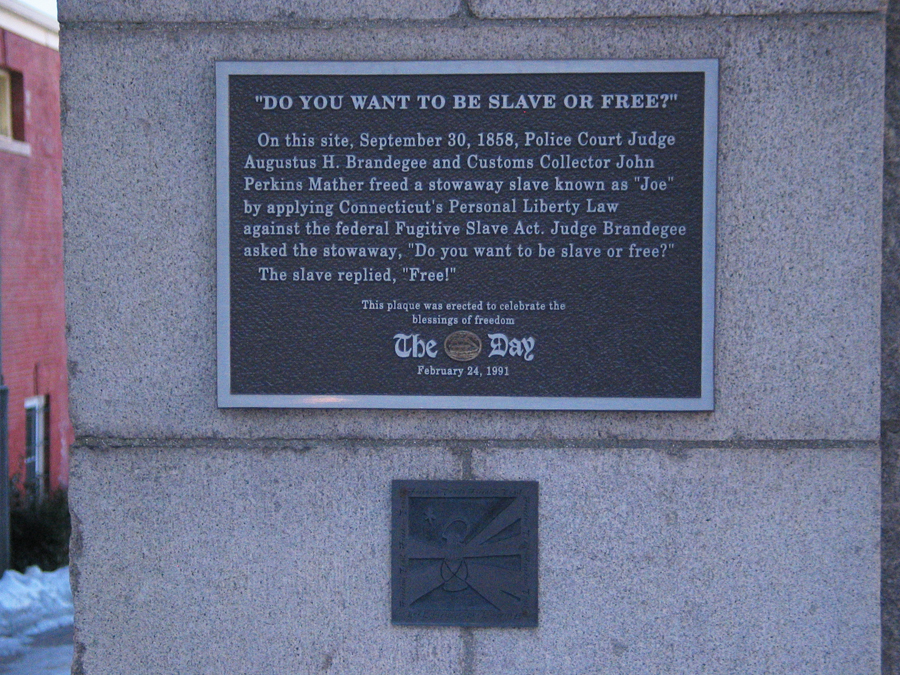

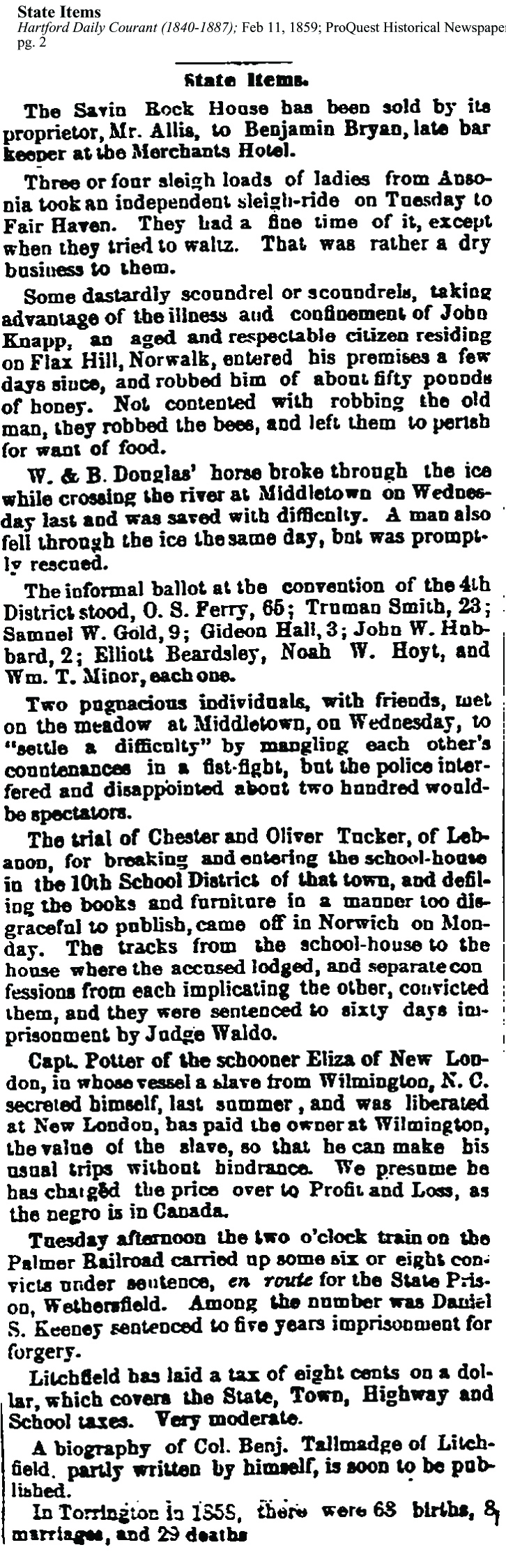

Sources contradict each other, but either Brandegee or Mather then asked the fugitive “Do you want to be slave or free?” When he responded with “Free,” state law was allowed to trump federal. Judge Brandegee told the captive to be off, and Benjamin Jones gained his freedom. The local newspaper reported that Jones then headed North through the town of Salem, but no oral history or document has been found recording who helped him or what happened to him. Five months later, the Hartford Daily Courant reported that Captain Josephus Potter paid $1,500 to Jones’s former slave owner, so he could continue his usual merchant trips without hindrance. The newspaper slyly noted, “We presume he [Potter] charged the price over to Profit and Loss, as the negro is in Canada.”

There are many remaining questions about Benjamin Jones and his flight to freedom. Who helped him board the schooner in Wilmington and how did he avoid the fumigation/inspection for stowaway slaves that the port performed on Northern-bound vessels? How did he get ashore once the schooner was moored and the captain went ashore to fetch a federal official and arrest Jones? How did he make his way from the east bank of the Thames River to downtown New London on the west bank, when there were no bridges across the deep river? What role did the black community in New London or free black sailors ashore play in helping him before and after his release? Did he really head North inland, or did he leave New London on a vessel from one of the piers within sight of the Custom House? Did he go to Canada, join one of the local Indian tribes, sign aboard a whaleship and settle in Hawaii or another foreign port? The hope is that further research will add to the museum’s and public knowledge about this interesting Underground Railroad case and how it intersected with the region’s strong maritime nature.

CHRONOLOGY OF EVENTS - the Amistad & Benjamin Jones in New London

August 27, 1839: La Amistad seized and brought to New London, CT.

August 1839: Judge Judson holds court of inquiry aboard survey brig USS Washington in New London harbor: New London abolitionist Janes learns the captives were not Cuban-born but free-born West Africans

September 1839: Amistad court case begins.

October 1840: Amistad sold; cargo auctioned on Customs House front steps.

November 1841: Africans and their supporters charter a passage back to Africa.

1848: Connecticut Personal Liberty Law passed.

1850: Federal Fugitive Slave Act passed.

August 1858: “Fugitive slave” Benjamin Jones stows away on Eliza Potter. Discovered en route, flees vessel and is later recognized in New London store and taken to Customs House for arrest and passage on revenue cutter.

Early 1859: Capt. Potter of the Eliza Potter pays $1,500 to Jones’ former owner in North Carolina.

We thank Elysa Engleman's UCONN-Avery Point Spring 2010 class in

Public History for making the museum the focus of a service-learning project:

to research Benjamin Jones & create the application to the National Park Service

that put the Custom House Maritime Museum on the Underground Railroad

Network to Freedom.

We officially received that national designation in October 2010.

The Custom House Maritime is the first of only two Connecticut sites on the

Robert Stanton: These places make real those struggles and triumphs. Without them they are easily forgotten, but with them, there is no more potent place to learn. In a real sense the preservation of historic places are more than the protection buildings, artifacts and landscapes. They demonstrate the value of diversity and community that honors and link us with the heritage of our predecessors. It seems to me that one of our greatest accomplishments as nation is that we have come to recognize that our legacy is about learning and teaching. Helping our youth find a better and a better place, a better environment, a better respect for ourselves and others because you and I have made our contributions.

Robert Stanton, from the U.S. Dept. of the Interior Web site, 10/06/2009

Robert Stanton, the Deputy Assistant Secretary of the U.S. Interior Department, is the former Director (and first African-American Director) of the National Park Service (NPS). He served as Director of the NPS at the time Congress passed the legislation to establish National Park Service's National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom Program.